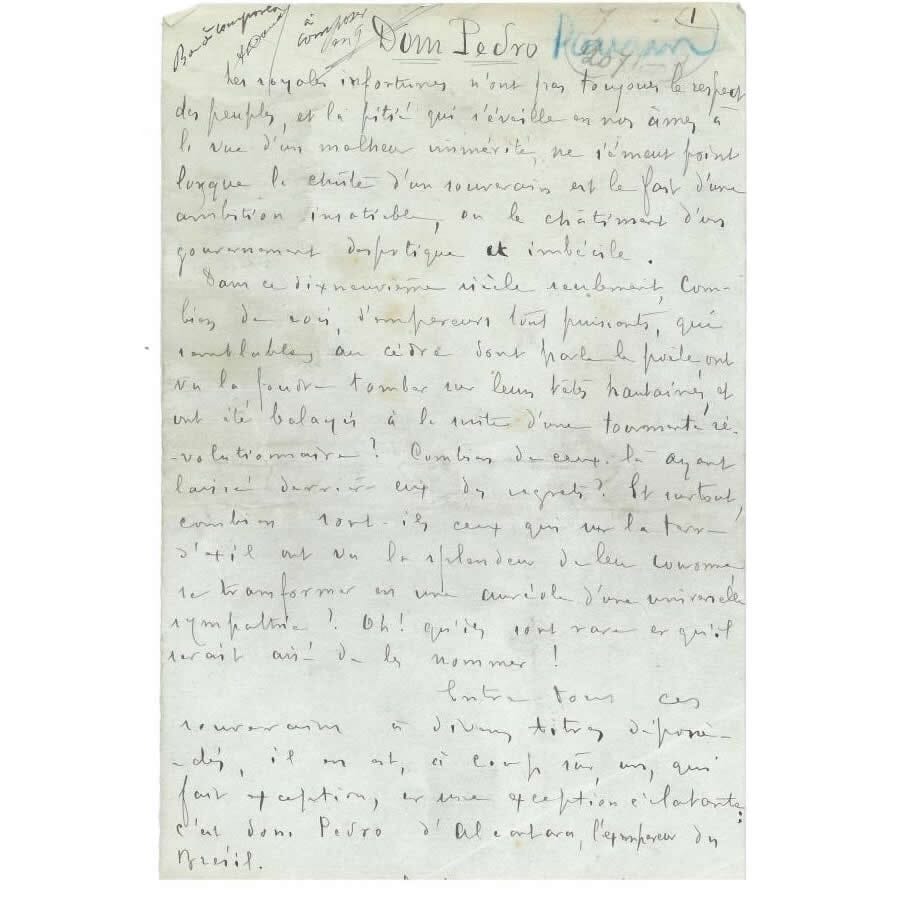

Necrology of Dom Pedro II (1891)

Necrology of Dom Pedro II (1891)

Free shipping

Comes with Certificate of Authenticity and Digital Warranty ©

Couldn't load pickup availability

In his obituary of Dom Pedro II, a close friend of the French writer George Sand reveals many previously unpublished details about the emperor's life.

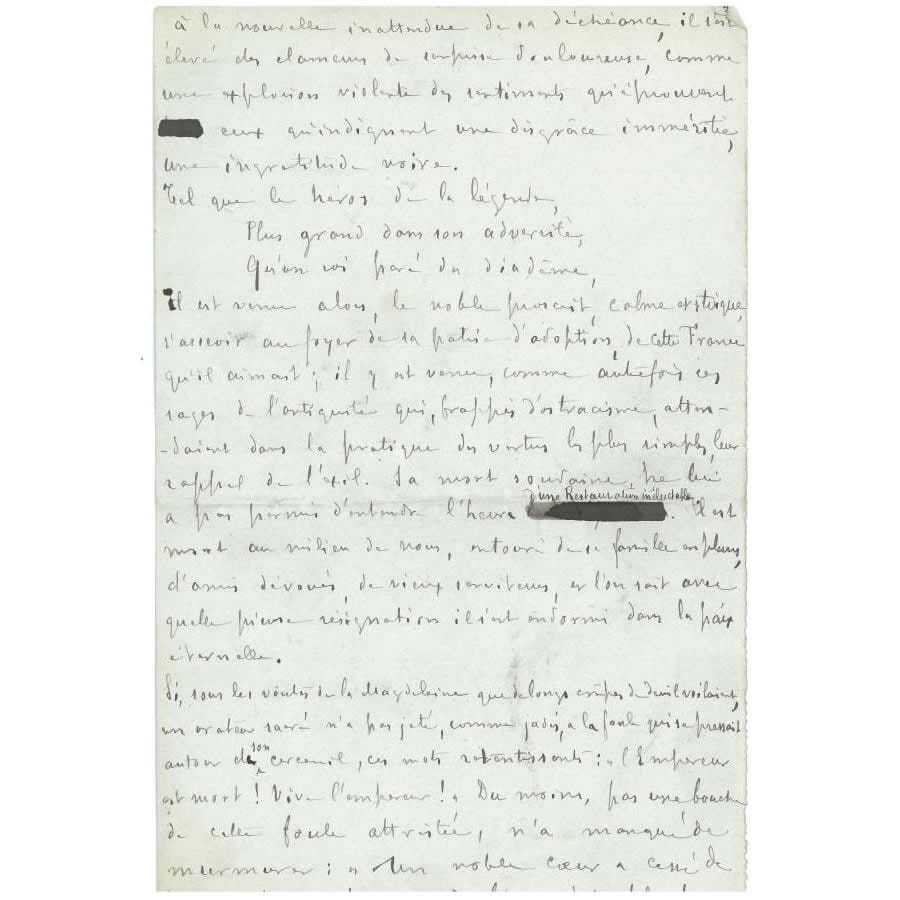

- Obituary of Dom Pedro II by Edmond Planchut.

- 12 pages.

- In French.

- 13.6 cm x 21.2 cm.

- France, Cannes region, 1891.

- Excellent condition of conservation.

- Unique piece.

Excerpts

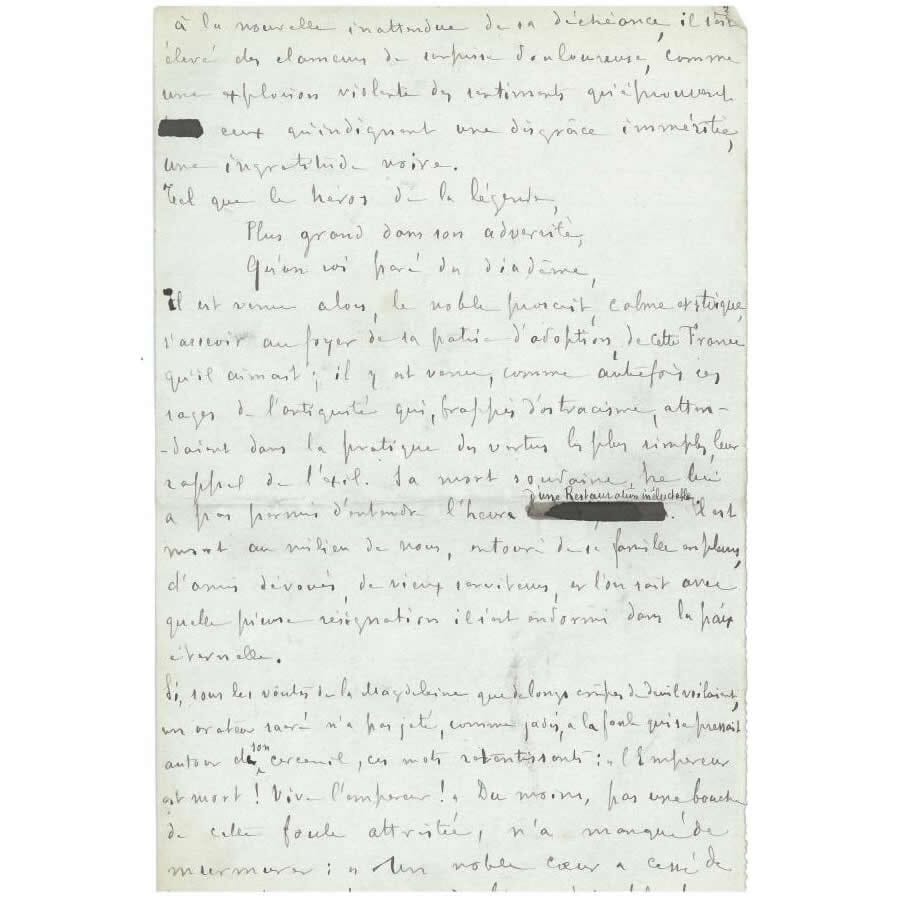

In the 19th century alone, how many kings, powerful emperors, similar to the cedar, as the poet says, saw the sickle fall on their proud heads and were swept away as a result of revolutionary turbulence? (...) Among all these sovereigns of various dispossessed titles, there is certainly one who is an exception, a notable exception: Dom Pedro de Alcântara, the Emperor of Brazil.

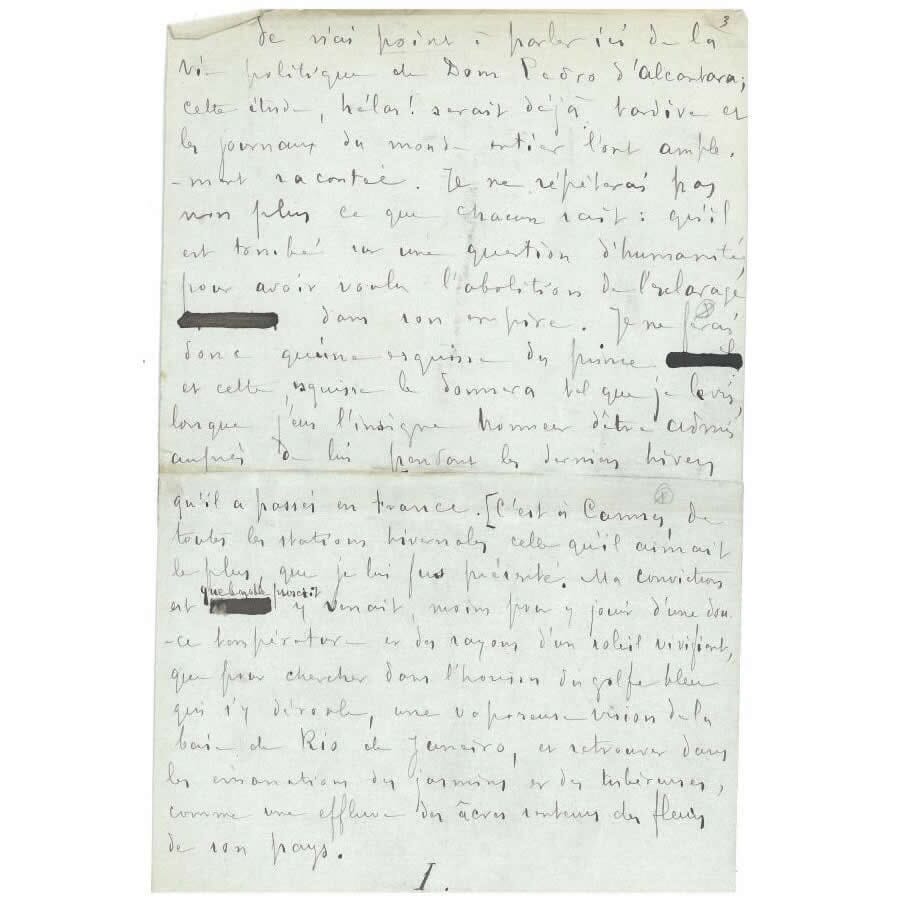

I will therefore only sketch the prince, and this sketch will describe him as I saw him when I had the honor of being admitted during the last winters he spent in France. It was Cannes, of all the winter resorts that were offered to him, that he loved the most. My conviction is that the noble outcast came less to enjoy a mild temperature and the rays of a vivifying sun, than to seek on the horizon of the blue gulf that forms there, a vaporous view of the bay of Rio de Janeiro (...).

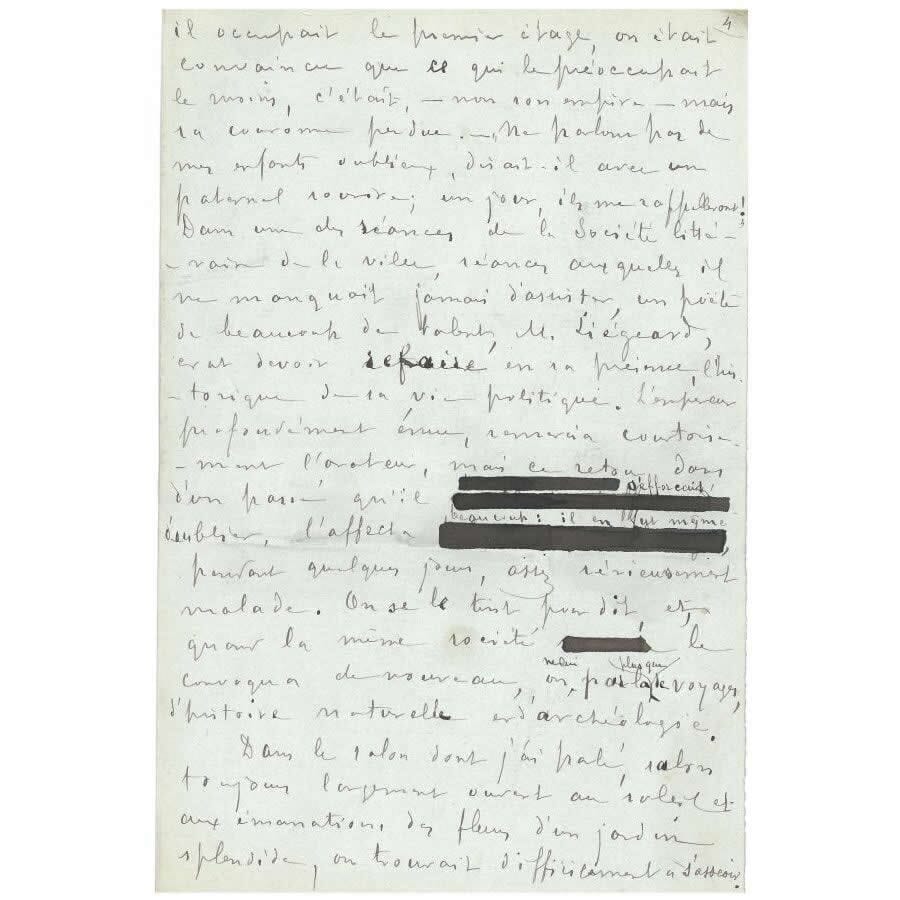

After a few minutes of conversation with Dom Pedro, in the lounge of the hotel whose first floor he occupied, we were convinced that what worried him least was not his empire, but the lost crown (...). At one of the sessions of the city's literary society, in which he never failed to participate, a talented poet, M. Liegeant, felt it his duty to tell in his presence the story of his political life. The emperor, deeply moved, thanked the speaker courteously, but this return to a past that he had tried to forget affected him greatly: he was even, for a few days, seriously ill. It was said, and when the same society summoned him again, they spoke only of travel, natural history and archaeology.

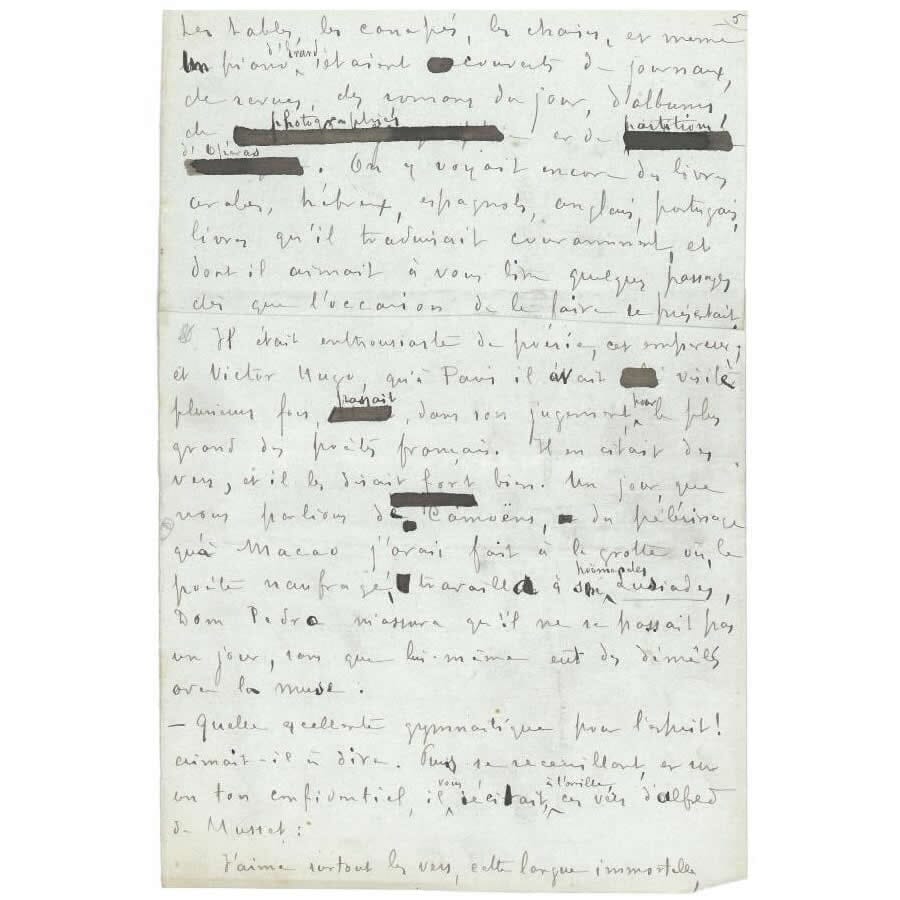

In the living room I mentioned (...), the tables, sofas, chairs (...) were covered with newspapers, magazines, novels of the day, photographs and opera scores. There were also the books in Arabic, Hebrew, Spanish, English and Portuguese that he translated fluently and from which he liked to read passages whenever the opportunity arose.

This emperor was enthusiastic about poetry and came to consider Victor Hugo, whom he visited several times in Paris, as the greatest of French poets.

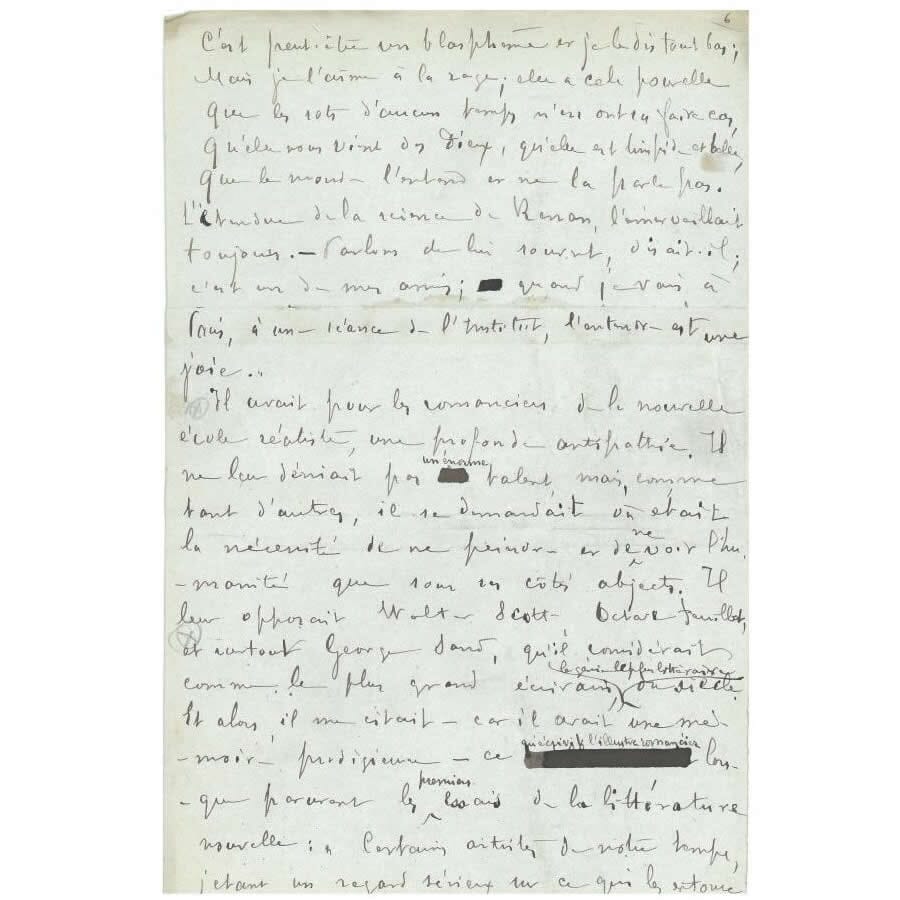

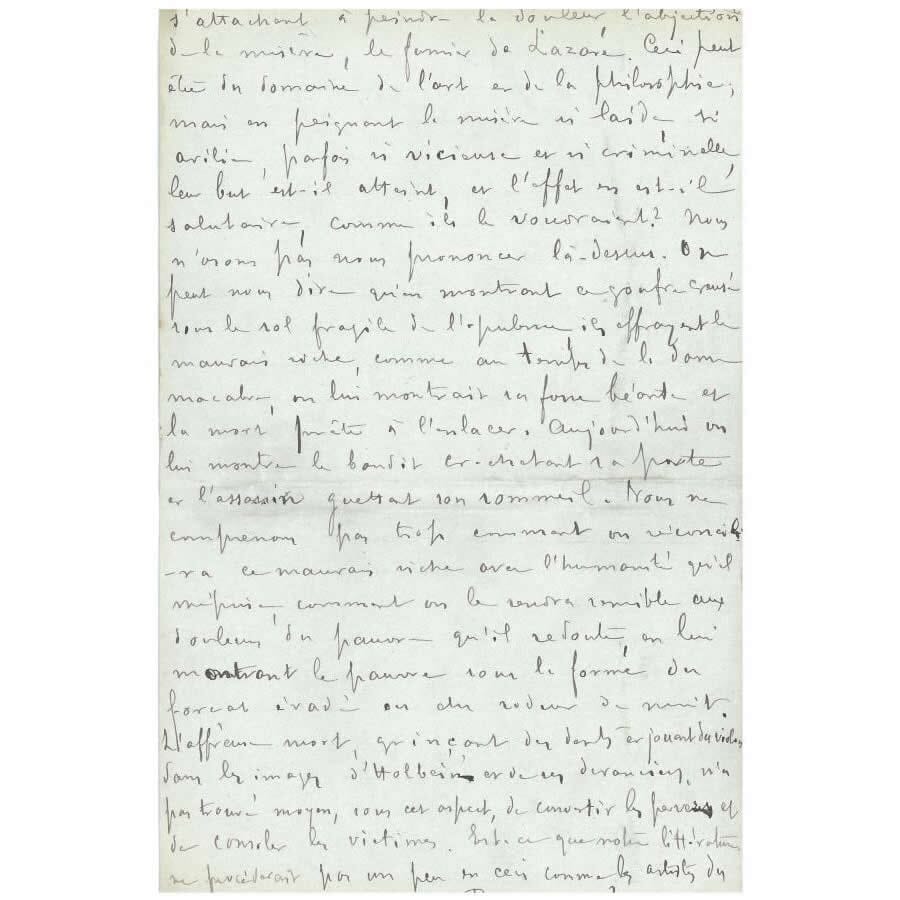

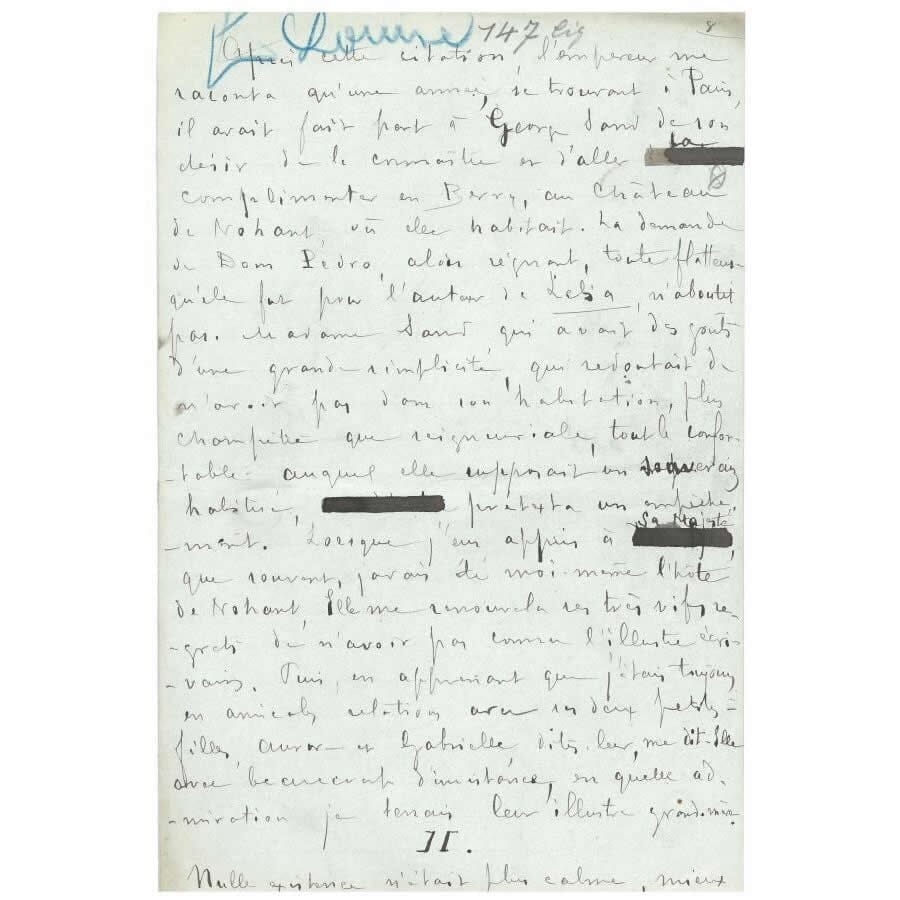

He had a profound antipathy towards the novelists and the new realist school. He did not deny that they had enormous talent, but, like so many others, he wondered where it was necessary to pretend and see humanity only from its abject sides. He compared them to Walter Scott, Octave Feuillet and especially to George Sand, whom he considered the greatest writer, the most literary genius of the century. And then he quoted to me, since he had a prodigious memory, what the illustrious writer wrote (...).

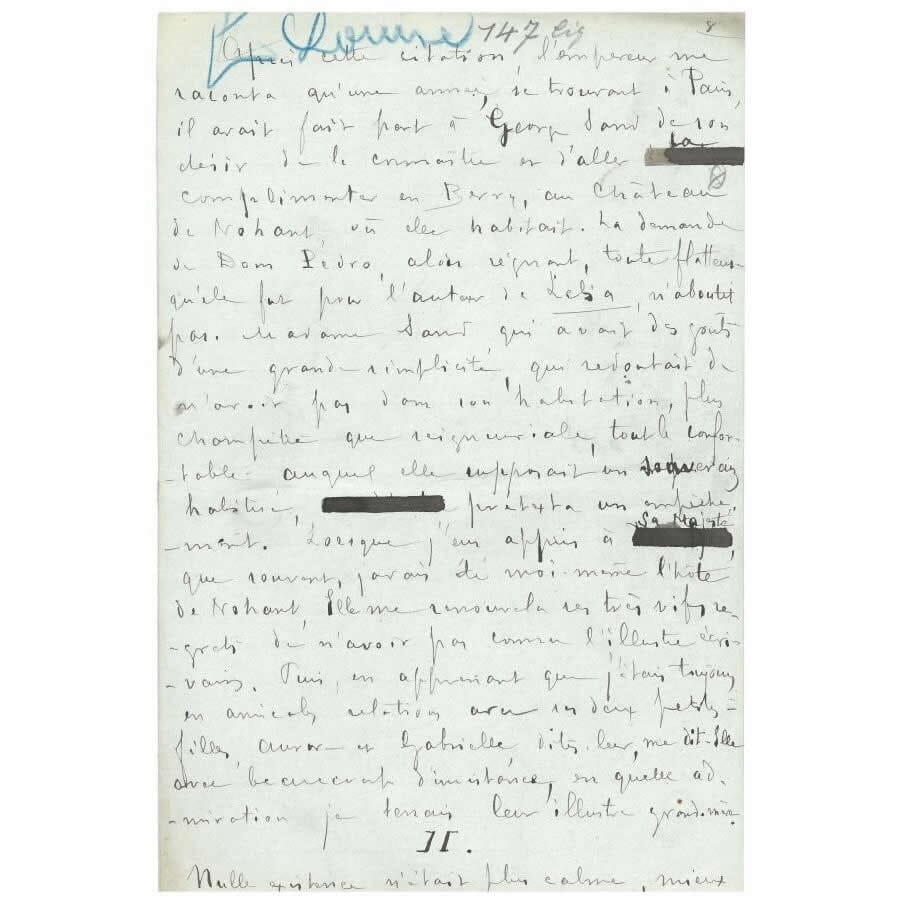

(...) He had told George Sand of his desire to meet and greet her in Berry, at the Château de Nohant, where she lived. Dom Pedro's request (...) was unsuccessful. Madame Sand, who had great simplicity of taste, feared that her dwelling, which was more rural than stately, would not have all the comforts to which she supposed a sovereign was accustomed, and feigned an impediment. When I mentioned to His Majesty that I had always been Nohant's host, the Emperor renewed his deep regret at not having met the illustrious writer. Then, upon learning that I had always maintained friendly relations with his two granddaughters, Aurore and Gabrielle, he asked me to tell them, very insistently, the admiration he had for their illustrious grandmother.

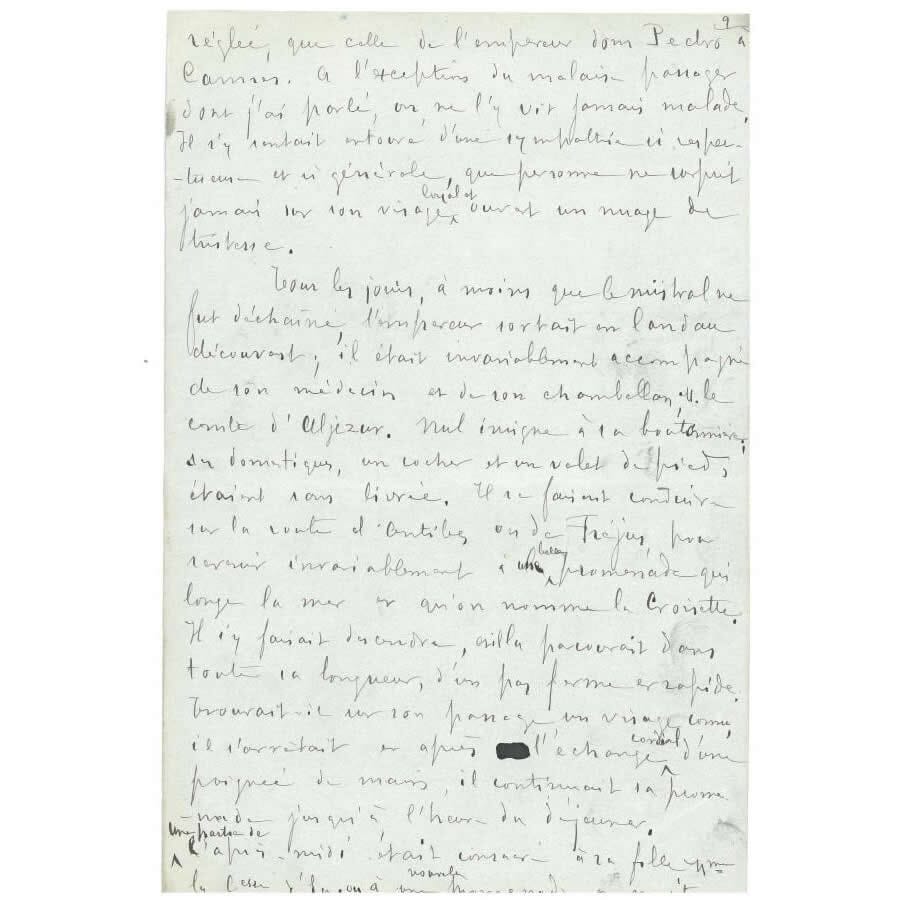

No existence was calmer, better organized, than that of the Emperor Dom Pedro de Alcântara. With the exception of the temporary discomfort of which I have spoken, we never saw him ill.

Every day, unless the wind was very strong, the Emperor would go out (...); he was invariably accompanied by his doctor and his valet. No medal on his coat (...). He would have himself driven along the road to Antibes or Frejus, returning invariably by a beautiful promenade that runs along the sea and which is called La Croisette, (...), with a firm and rapid step. When he met a familiar face on his way, he would stop and, after a cordial exchange, with a handshake, he would continue his walk until lunch. Part of the afternoon was devoted to her, Madame Countess of Anjou, in a new drive.

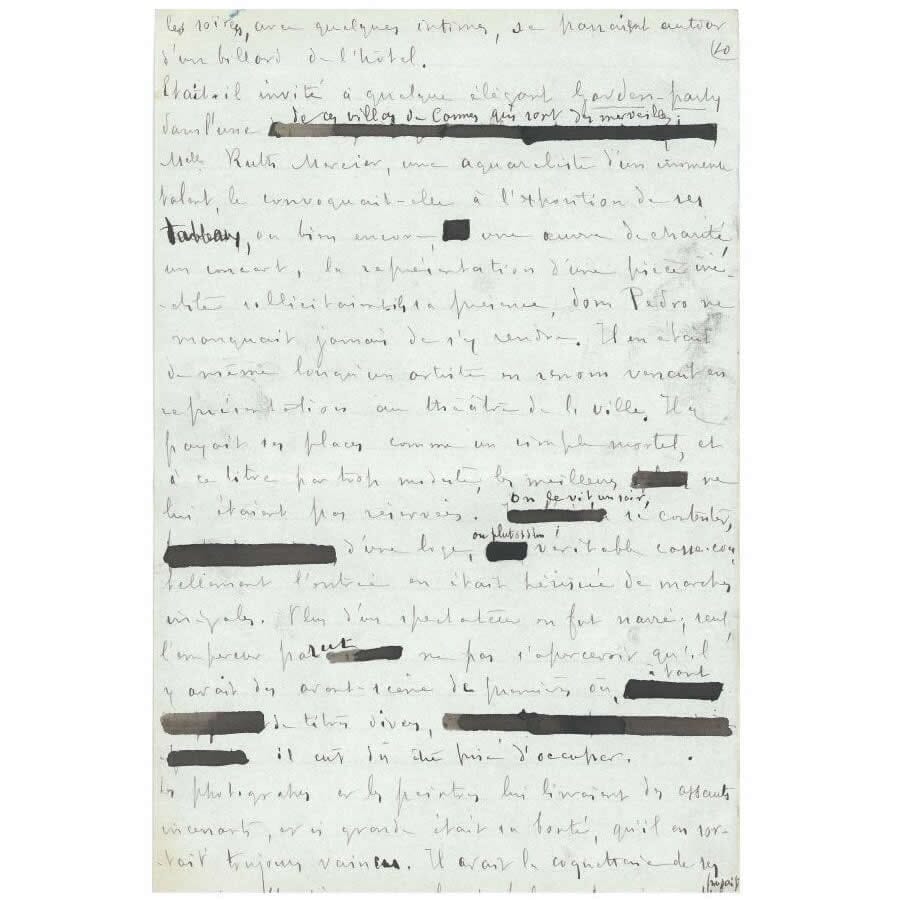

The evenings, with a few close friends, were spent around a billiard table at the hotel. He might be invited to an elegant party at one of those marvelous villas in Cannes. Miss Ruth Mercier, a watercolourist of immense talent, might invite him to an exhibition of her paintings. Or he might be invited to a charity event, a concert, or the performance of a new play; Dom Pedro never failed to go. The same thing happened when a renowned artist came to play at the city theatre. He paid for the tickets like a mere mortal and, as such, very modest, the best seats were not reserved for him. One evening he was satisfied with a lonely seat (...), whose entrance was bristling with irregular marches. More than one spectator was saddened; only the Emperor seemed not to mind (...).

Photographers and painters approached him incessantly, and so great was his kindness that he always gave himself up. He was about fifty years old, and really very handsome. One day, when he was posing for a painter friend of mine, His Majesty said to me in a foreign language, so as not to be understood by the artist:

"Whose hands is this man painting, see if they look like mine?"

All those pastimes to which he indulged out of kindness, and also out of love for everything that was far from or near literature and science, did not prevent him from following with interest what was going on under the dome of the Institute. It was as he was leaving, barely covered, one of the sessions of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, of which he was a member, that a shudder seized him and carried him to the grave.

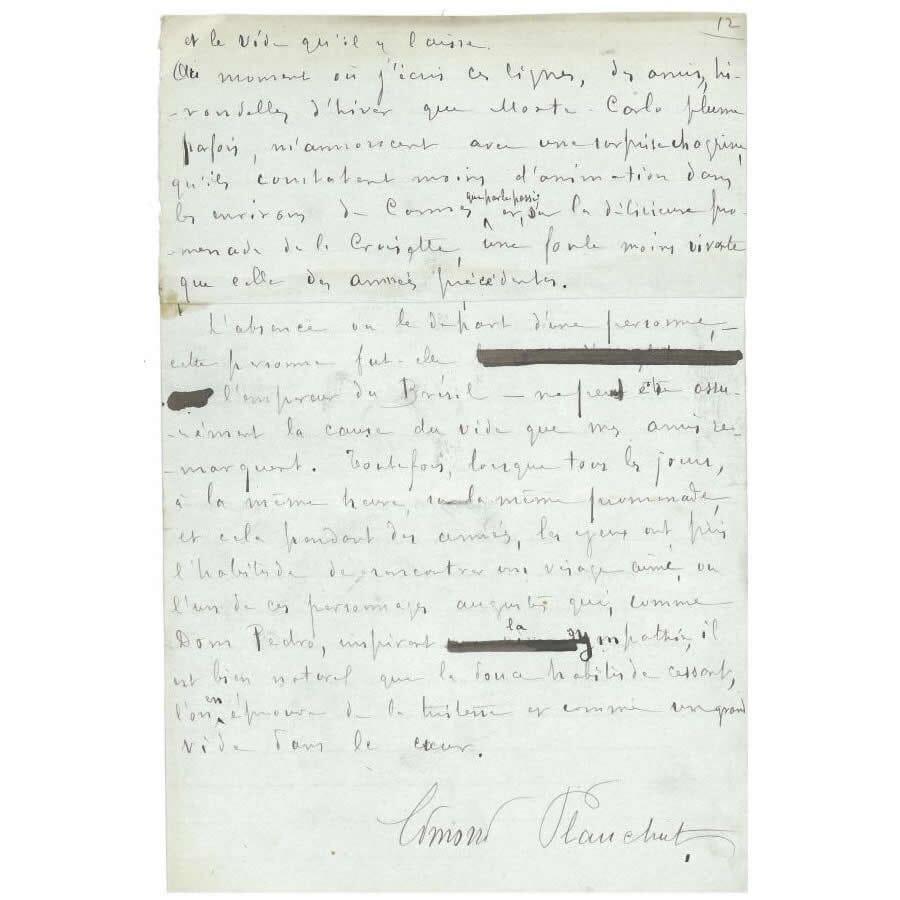

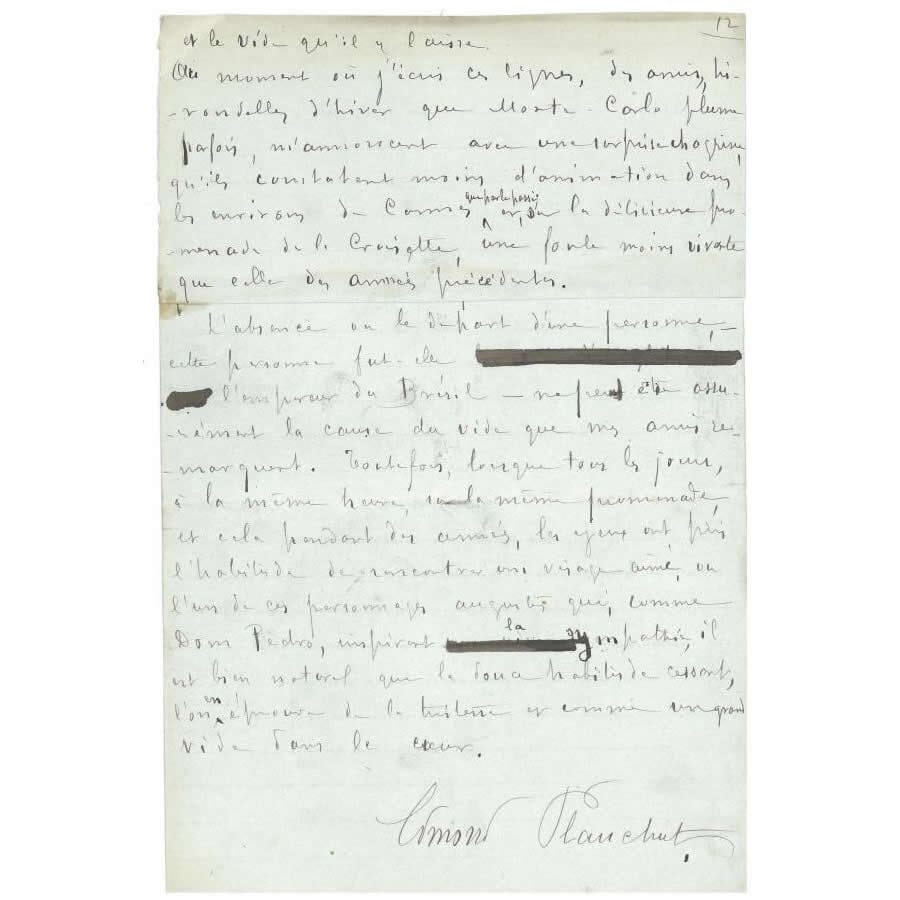

As in previous years, if he had returned before the first cold snaps of winter, the sunny path of the Côte d'Azur, Dom Pedro would still have been one of the most beloved guests. It should be added that the repercussions of the disturbances that once again shook Brazil reached him more quickly in Paris than on a distant beach, and this was undoubtedly what made him postpone his departure for Cannes. He should have lived there only for the memory and the emptiness he left behind. As I write these lines, friends (...) announce to me with sad surprise that they find less excitement in the vicinity of Cannes than in the past and, on the charming promenade of the Croisette, a less lively crowd than in previous years.

The absence or departure of a person, even the Emperor of Brazil, certainly cannot be the cause of the emptiness that my friends perceive. However, when every day, at the same time, on the same walk and for years, our eyes have become accustomed to encountering a beloved face, or one of those august personages who, like Dom Pedro, inspire sympathy, it is natural that when the habit ceases, we feel sadness as a great emptiness for the heart.

Edmond Planchut was a journalist and adventurer, a close friend of the brilliant and scandalous French writer George Sand (1804 - 1876) and her daughters. Sand was a pioneering feminist whom Dom Pedro II admired, something that Princess Isabel disapproved of, as evidenced by a letter from her to her father: "Not a single word for me, and he finds time to go and visit George Sand, a woman of great talent, it is true, but also so immoral! (...) No matter how incognito he goes, one always knows who Mr. Dom Pedro de Alcântara is, and shouldn't he be, above all, a good Catholic and, therefore, keep away from himself anything that is immoral?"

This text is a precious testimony about the Emperor of Brazil, written by someone who lived directly with him in Cannes, in the south of France, for months. The simple tastes and modesty of the Emperor, despite his prestige and immense culture, his admiration for the writers George Sand and Victor Hugo, his pleasure in coming to Cannes for long walks, his longing for Brazil and its people and, finally, the circumstances of his death and the impact it had on France, draw the attention of the reader who holds this exceptional document in his hands.

Assine nossa newsletter

Achamos tesouros todo mês. Seja o primeiro a saber.